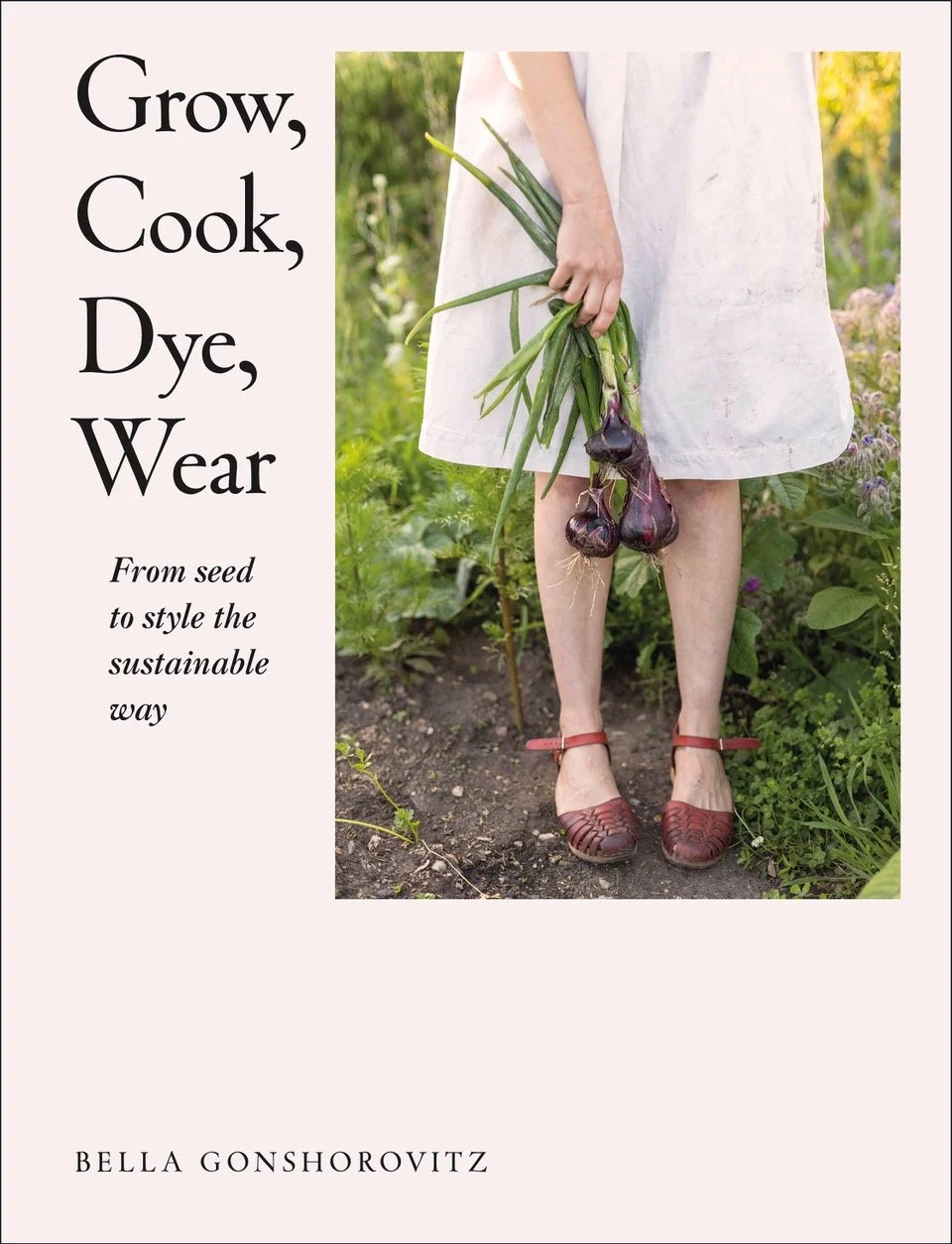

Grow, Cook, Dye, Wear: Bella Gonshorovitz

Image: Julius Honnor

In the search for viable new fashion systems, designers are finding themselves tracking change all the way down the supply chain - to the materials and the fibres that create them themselves. Fibreshed is one example; the extraordinary work by Amy Powney at luxury label Mother of Pearl is another. In her debut book, “Grow, Cook, Dye: From seed to style the sustainable way”, award-winning designer Bella Gonshorovitz embodies these aims, depicting a ‘seed to garment’ circular economy cycle, using just five crops. They are cottage garden plants we barely notice - onion, nettle, rhubarb, blackberry and red cabbage - but Gonshorovitz brings their potential to life.

A long time vegan, growing produce in her allotment in Higham Hill Common allowed Gonshorovitz to experiment with different crops in the garden and in the kitchen. In the book, she charts a practice-based approach, starting with a guide of growing your own (or foraging), before using the harvest itself in simple recipes and the food waste to create natural fabric dye. Finally, full-size dressmaking patterns and illustrated instructions allow you to make your own Onion dress, Nettle duster, Rhubarb bolero, Blackberry shirt(dress) and Cabbage shorts. The aim is for the reader to end up with a true 'slow fashion' garment imbued with the growing experience and to reconnect with the notion that all we wear, eat and consume comes from nature.

Bel: After a degree in fashion design at the Instituto Marangoni, working for threeASFOUR and Alexander Wang in New York, you studied Innovative Pattern Cutting as a postgraduate at Central Saint Martins and gained an MA in Applied Psychology in Fashion at LCF. Tell me about your journey from that point.

Bella: I started my own made-to-measure studio - reluctantly at first, because I didn’t want to let go of design and fashion, as I perceived it then, and become only a dressmaker. However, once I started doing it, it solved a lot of problems I had thought of as ethical but which were actually sustainability issues.

I’d worked with fantastic brands that had produced, for the most part, in very thoughtful ways (I’m not going to say sustainable because it was a different time). But there were always styles that didn’t work or weren’t commercial. Every brand would end up with rooms full of [excess] stock and I began to feel that design was, in a way, a vanity. I started feeling wrong, in an intuitive way.

That's when I got involved with the Centre for Sustainable Fashion and it all clicked. [Time at CSF] allowed me to explore the emotional connection we have to clothes, within the context of sustainability.

A strong part of why I wanted to design in the first place, why I wanted to make clothes, was [to look at] how clothes become memory. I wear things for decades. Even if they don't fit anymore, I find a way to adjust them. I can't let go of things and if something gets lost, I’m devastated. When fast fashion became so big, I was just staggered that people could buy something and then just throw it away. Clothes are imbued with what you had with the garment.

Bel: How did the book come about?

Bella: I had the title ‘Grow, Cook, Dye’ in my head and thought ‘what am I going to do with it?’ I was growing vegetables in my allotment and working with natural dyes. And, at the same time, I started making artwork with a client of mine, an artist called Cathie Pilkington. And I just started connecting the dots between growing things and cooking things and dyeing clothing.

Initially, I thought I should have a supper club where people could come, eat the food and then buy the clothes. But that’s not really my goal because I'd still be putting stuff out there. Then, during the first lockdown, I thought, ‘that’s the way to imbue the garment with the growing experience and the cooking experience.’ You have the journey already. It carries all this memory of the process and it gives you a different perspective to what a dress can be - and, hopefully, it gives the readers a different perspective on clothes they see in shops.

Bel: It’s nice to meet a fellow vegan!

Bella: I’ve been vegan for 14 years now. There’s been such a shift in attitudes towards veganism. Now, it's something that people are keen to experiment with, which is fantastic.

Bel: You’re one of a number of designers who’ve found themselves going back to the land. It’s a radically different way of thinking about fashion. So who is this book for? The curious, the experienced, the novice, the concerned?

Bella: [The book] is for anyone who enjoys doing things with their hands. The book doesn't ask you for expensive ingredients or special knowledge. It's about doing quite a lot with very little, with a real emphasis on upcycling and working with what’s already there, whether that’s an old sheet or tablecloth.

The purpose of the book is not for everyone to grow all their vegetables or to make all the clothes or even convert to a strict vegan diet. It’s getting this perspective and making you ask what goes into the clothes we wear. So I hope that the audience will be quite broad; that some people will hopefully enjoy it as a good read and others might pick it up and think, ‘Oh, it's a beautiful book, maybe I will do something in it’. But I hope that as many people as possible will engage with it because that’s its real purpose.

That’s why I spent a long time on the sewing illustrations. If you don’t know how to sew at all, it’s probably not the best place to start, but if you have some experience, the onion dress is probably the easiest project. And the wonderful thing about natural dye is that, if you do have an old cloth that is imbued with memory and some stains, the dye works quite well with it.

You have to have a willingness to engage. You might just cook a couple of recipes or you might experiment with dying. You need to be open to investing time. That's the most expensive ingredient in the book: time.

Bel: You’re interested in the similarities between growing and the circular economy.

Bella: I like to use soil as a metaphor for the circular economy because soil beautifully demonstrates quite academic terms of how you have circularity in design: everything that comes from the soil goes back to the soil. It’s very humbling. Take horse manure, for example. It’s the most precious thing in the allotment. In the modern world, we wouldn’t think about it twice but, here, it’s this incredibly valuable resource.

In the same way, natural fabrics can go back to the soil. I find that so moving - and a really straightforward way to understand the idea of [circular economy]. When I hear the term ‘economy’, I think about numbers - and I’m not a numbers person. But in the soil, it just made such clear sense.

Bel: As you’re speaking, I think about the way we buy off the rack, everything is the same. Your book speaks to people who are happy to encounter the unexpected - because you can’t always predict how the dye is going to attach to the fabric. And I’m really enamoured with the idea of experiential learning, where you get your hands in the soil and where you might ‘fail’. You have to start to ask yourself what ‘failure’ is. Is it a mistake just because it isn’t like everything else? I’d argue not. The other thing I noticed is this idea of using every part of the plant. This is deliberate?

Bella: Yes. And this is the right moment for [this type of thinking]. If I’d published two years ago, it would have felt really niche. The struggle that a lot of publishers had with it was, ‘is it a cookery book, a garden book, a fashion book, a craft book?’ I constantly had to say, ‘well, it sits on all those shelves. It shows how all these things connect.’ Connecting the dots is incredibly important if we're trying to tackle behavioural changes in climate.

It’s a big conversation, whether [change] is about human behaviour or policy. We have to have both. We live in this terrible system of capitalism, in the context of tackling climate. If we, as consumers, decide we want to act in certain ways, capitalism would listen. That’s why so many brands are trying to engage with sustainability, whether it's wholeheartedly or on the surface. To understand how things connect is really meaningful.

Bel: I agree. Personal action is important. For example, I’m vegan because I don’t want to cause animal suffering. It would actually be quite difficult for me now to eat the body of an animal. Animal suffering and eating meat and dairy are inextricably linked. Likewise, if you know that the clothes you’re buying have been produced in a polluting, extractive, exploitative way, it should be quite difficult to buy them. I also tend to think of consumer responsibility as modelling new ways of living in the future. Because we need to learn to live in these ways now. Plus, in this time of crisis, we have to have everyone - ordinary people, policy makers, brands. So the re-education you talk about is key.

Bella: Yes. Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything was a pivotal point for me - as was working with the Centre for Sustainable Fashion. But also, I find so much joy working this way. I wouldn’t want to ‘go back’ because, as you say, I just don't see that as a feasible way to live and be happy. I wanted to bring that to the book as well; to send that message in a way that is inclusive and heartwarming and not just saying, ‘we have to stop doing this’ but to say ‘look at all the beauty and joy you will find, if you can engage with this experience.’

Image: Julius Honnor

Image courtsey of DK/Penguin Random House